Rights to Privacy

By Paul Martin Lester

Photojournalism An Ethical Approach

(c) 1999

When victims of violence and their families, through no fault of their own, are suddenly thrust into the harsh light of public scrutiny, they often bitterly complain. Their private life is suddenly the subject of front-page pictures and articles. Readers are quick to react when they feel a journalist has crossed the line and intruded into a subject's personal moment of grief. Anne Seymour, public affairs director for the National Victim Center in Fort Worth said, "Any time there is a yellow line, some journalists in the interest of news will cross over" (Zuckerman, 1989, p. 49).

Public officials and celebrities also feel that journalists sometimes cross that yellow journalism line in covering their everyday activities. Television actress, Roseanne Barr, who frequently advocates her and her family's right to privacy, told a story on the "Oprah Winfrey Show" (1989, November 20) that illustrates this point. Her mother saw a television camera, Barr said, coming through the window of her home. Barr's mother was forced to lie on the floor to avoid being videotaped.

The judicial system in America has recognize that private and public persons have different legal rights when it comes to privacy. Privacy laws, as can be imagined, are much stricter for private citizens not involved in a news story than for public celebrities who sometimes invite media attention. Journalists need to be aware of the laws that are concerned with privacy and trespass. But ethical behavior should not be guided by what is strictly legal.

PRIVACY IS AN EARLY ISSUE

Historically, invasion of privacy issues are linked with candid photography. Limitations with the type of camera, lenses, and film in the early days of photography prevented many of the candid moments that are commonplace today. Once cameras became hand-held and lenses and film became faster, amateur and professional photographers were able to make pictures that previously were impossible.

Early news photographers were forced to use bulky cameras that limited the type of picture possible. Candid pictures were simply not possible when subjects quickly spotted a photographer. The photographs of Paul Martin and Jacques-Henri Lartique stand out as wonderful exceptions. They captured many candid moments among 19th-century citizens.

Typical subjects of Martin's candid style were Victoria-era children playing in public parks, women enjoying the surf during holidays, and men working along the busy streets of London (Flukinger, Schaaf, & Meacham, 1977).

It was rare when a photographer could capture a spontaneous news event. More likely, subjects in news and feature assignments were carefully composed by the photographer to create a static or stereotyped look. As Wilson Hicks (1973), author of Words and Pictures wrote, "Instead of picture consciousness, it was a time of camera consciousness. Practically everybody looked at the camera. . . . When the photographer entered a situation of movement involving people, life stopped dead in its tracks and orientated itself to the camera" (pp. 26-27).

The successful documentary photographers during the early years of newspaper photojournalism were the ones who could make pictures that did not have a highly manipulated look. Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine were photographers who used the equipment of their day-large, bulky cameras with slow film and lenses. Although their photographs, for the most part, showed individuals and groups looking into the camera's lens, their pictures are classic documentary statements because of the lack of manipulation by the photographers. It is a rare occurrence to find images by Riis or Hine that show subjects unaware of the camera's presence.

Lewis Hine, of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, worked in a factory for long hours during the day when he was a boy. Consequently, his photographs of children suffering for many hours at low pay and with dangerously, fast-moving machines were vivid and disturbing. Child labor laws were passed to protect children, a direct result of his photographs (Pollack, 1977, pp. 91-93).

George Eastman's Amateur Craze

The invention of a faster dry plate film meant that medium-sized and smaller, handheld -cameras could be used. Such cameras allowed amateur and professional photographers to make pictures of unsuspecting subjects. George Eastman came up with a camera he dubbed, the Kodak. The Kodak slogan was, "You push the button-and we do the rest." The camera was small, easy to use, and contained 100 pictures on a dry gelatin roll. When the snapshot shooter had exhausted the roll, the camera was mailed to Rochester, New York where the film was processed, printed, and returned to the owner with the camera and a fresh roll of exposures.

Amateur photographers immediately took snapshots of practically anything that moved with the little Kodaks and other cameras. No one was considered safe as unsuspecting strangers clicked off exposures. The camera craze that began in the 1880s was an international epidemic that prompted retaliation by those upset with photographers taking candid pictures of people without permission. The New York Times "likened the snapshot craze with an outbreak of cholera that had become a I national scourge' " (Jay, 1984, p. 10). A popular poem, a parody of the Kodak slogan was,

Picturesque landscape,

Babbling brook,

Maid in a hammock

Reading a book;

Man with a Kodak

In secret prepared

To picture the maid,

As she sits unawares.

Her two strapping brothers

Were chancing to pass;

Saw the man with the Kodak

And also the lass.

They rolled up their sleeves

Threw off hat, coat and vest

The man pressed the button

And they did the rest! (Jay, 1984, pp. 11-12)

Vigilante associations were formed to protect the honor of unsuspecting women. A brick thrown through a camera's lens was advocated as a possible remedy. The Chicago Tribune wrote in an editorial that "something must be done, and will be done, soon. . . . A jury would not convict a man who violently destroyed the camera of an impudent photographer guilty of a constructive assault upon modest women" (Jay, 1984).

A photographer intent on capturing people in embarrassing or compromising situations was despised by a great many people. Although anti-photography bills were never introduced in America, Victorian London photographers required free official permits to take pictures in parks. Restrictions often included "Persons and groups of persons . . . on Sundays . . . [with] hand cameras" and without tripods (Flukinger et al., 1977). Germany passed a statute prohibiting photography without permission in 1907.

Of newspaper and magazine photographers who put small cameras to use, Bill Jay (1984) in his article, "The Photographer as Aggressor," wrote, "As any impartial observer will admit, no aspect of a life was too private, no tragedy too harrowing, no sorrow too personal, no event too intimate to be witnessed and recorded by the ubiquitous photographer" (p. 12).

Small, hand-held professional cameras, particularly those made by the Leica company, made it possible for photographers to take high quality pictures of people in low-light situations without a subject's knowledge or consent. Two early prolific and respected users of the small cameras were Paul Wolff and Erich Salomon. Wolff became known for his feature pictures where he, according to Hicks (1973), showed that a picture could be made out of any subject. Salomon, a lawyer who took up photography to earn a living after the loss of his family's fortune, made unposed pictures of presidents and statesmen during meetings and public functions. Salomon's images are beautifully composed candid moments of hard-talking politicians caressed by the gentle glow of available light. His photographs were published in several illustrated German publications and became a model for candid pictures for future generations of news photographers. Salomon's photographic career was tragically cut short when he was captured and executed by the Nazis.

Privacy violations would not became an issue if it were not for editors who were willing to publish the revealing, hidden moments. Magazine and newspaper editors once the halftone process became relatively inexpensive and aesthetically acceptable, were eager to fill their pages with photographs that were used, admittedly, to sell more copies. Hicks (1973) summed up the philosophy of the editors of the day with, "Get the picture-nothing else mattered" (p. 25). This was the era of the scoop. Competition was so fierce that photographers would go to great lengths to beat a rival photographer. One of the best known freelance newspaper photographers, Arthur Fellig, gained his reputation for taking pictures of accident and murder victims no one else had. Fellig's motto was, "F/8 and be there." Professionally known as "Weegee," a variation of the popular table entertainment, "Ouija," Fellig, aided by police informants, arrived at news events often before the police (Stettner, 1977).

The Courts Ban Cameras

The era culminated with the trial of Bruno Hauptmann for the kidnapping and murder of aviator, Charles Lindbergh's baby. Over 700 reporters and 125 photographers covered the sensational events of the trial. Although photographs were allowed in the courtroom before the trial, during recesses, and after the trial, there were many abuses by competitive-crazed photographers. After the trial, the American Bar Association issued the 35th canon of Professional and Judicial Ethics. Most states adopted Canon 35 to ban photographers from their courtrooms. Before the ruling, a judge could independently decide whether to ban news photographers.

In the 1950s, Joseph Costa and the NPPA lobbied to appeal the states' ruling. Slowly, acceptance for photographers' presence in the courtroom grew. Florida's cameras-in-the-courtroom model, approved by the Florida Supreme Court, was tested successfully during the Ronnie Zamora trial in 1978 (Kobre, 1980).

In another Florida case, the Supreme Court in 1981 upheld the conviction of two Miami Beach police officers for burglarizing a restaurant. Officers Noel Chandler and Robert Granger felt that they were denied a fair trial by the presence of television and still photojournalists in the courtroom. The Supreme Court allowed individual states to decide how to regulate the coverage of trials. Florida, as with many other states, does not require permission from all participants for photo news coverage, but restrictions were imposed. "Only one television camera and only one still photographer are allowed in the courtroom at one time. Equipment must be put in one place; photographers/camera persons cannot come and go in the middle of the proceeding, and no artificial light is allowed." Other states have opened up their courtrooms to photographers. Federal trials are still off limits for cameras (Nelson & Teeter, 1982).

As opposed to the small, 35mm camera, the bulky 4X5 press cameras were seldom used for candid images. The press camera was simply a hand-held version of the view camera that had to be set on a tripod. The camera only held one 4 X 5-inch negative holder with two sheets of film at a time. The negative holders were awkward to manage. There was no through-the-lens or rangefinder mechanism to aid focusing. After each exposure a new flash bulb had to be inserted into the flash unit while an unexposed film holder had to be inserted in the back of the camera. Despite the availability of small, hand-held cameras, a 1951 survey of 61 newspapers with circulation of over 100,000 showed that 97% of the staff photographers used the 4X5 press cameras (Horrell, 1955).

Arthur Geiselman of the York, Pennsylvania Gazette and Daily was attacked by a crowd at the scene of a child's drowning. "The 4 X 5 is not the camera for this kind of spot news coverage," wrote Geiselman (1959). "1 believe if I had had a 35 millimeter camera I could have avoided trouble. The clumsy, black box is too much in evidence at a time when a camera should be inconspicuous" (p. 13).

The subjects of the press cameras, were for the most part, aware of the photographer's presence, unless the subject was greatly preoccupied. Privacy problems arose when editors chose to use sensational pictures on their front pages. In an era of yellow journalism, photographs contributed greatly to the public's repulsion of news photography as a profession. Photojournalists were labeled as mindless ambulance chasers without a thought for the subjects of the images. As one writer (Edom, 1976) noted, photographers were considered "reporters with their brains knocked out" (p. 26). Such a characterization was misleading because reporters also wrote stories that contributed to the sensational era.

Should a News Subject be Compensated?

Photographers did produce moving photographic documents with large, press cameras, however. The Farm Security Administration (FSA) was a governmental agency set up by the Roosevelt administration to document the weather and economic affects upon people during "The Great Depression." Led by Harvard economics professor Roy Stryker, the photographic unit of the FSA included such household names as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee, Carl Mydans, and Arthur Rothstein.

One of the most memorable images of all time came from the FSA collection. Dorothea Lange made "The Migrant Mother," a sad, roadside close-up of a destitute mother with a faraway look and her shy children. Unfortunately, the mother in the portrait, Florence Thompson, complained that Lange received fame for the picture while she lived in relative poverty. Nevertheless, when Mrs. Thompson suffered a stroke and her family could not pay her medical expenses, people around the country donated over $15,000. Many wrote that they were touched by Lange's photograph (see Los Angeles Times, November 18, 1978, p. I and "Symbol of depression," 1983).

Newspaper photographers eventually replaced their 4X5 cameras with more easily manipulated 35mm cameras. Consequently, photojournalism reporting gained respect as many more photojournalists were more inclined to photograph people as they really were rather than stage direct a subject's actions. Private moments that involved social problems were now the subject of photographers. Picture magazines such as the London Post and America's Life and Look ushered in what many considered to be the "Golden Age of Photojournalism." Gene Smith, Margaret Bourke-White, Alfred Eisenstaedt, Leonard McCombe, and Bill Eppridge are some of the photographers that worked for the picture magazines.

Eisenstaedt's Time's Square celebration kiss between two strangers, a soldier and a nurse, beautifully shows the joy the world felt that World War 11 was at an end. The picture, however, has been embroiled in controversy as up to 10 sailors have claimed to be the man in the famous picture. The ultimate goal of the claims made by the soldiers is a percentage of the profits Time, Inc. has made throughout the years for the sale of the image.

Smith made classic picture stories of individuals: a country doctor and a nurse mid-wife are two of his favorite stories. McCombe produced one of the first "A Day in the Life" stories with his coverage of a young woman from a small town working in New York City. Bill Eppridge produced one of the most dramatic picture stories in the history of Life magazine. Headlined, "We are animals in a world no one knows," Eppridge and a reporter, James Mills, produced a sensitive and shocking portrait of a young, educated couple forced into prostitution and robbery to feed their $100 a day heroin addiction. Eppridge and Mills received permission to intrude into their daily lives without paying their subjects (Edom, 1980).

Robert Frank and Magazine Photography

Many photographers established a style of photography that was unique to the 35mm film medium. Their images were usually of people in bars or on the street who were unaware of the camera's presence. Inspired by the writings of "beat" novelist, Jack Kerouac, Robert Frank is best known for his gritty portrait of America contained in his book, The Americans. Frank spent more than a year "on the road" through a Guggenheim grant. He made pictures that showed a side of America that contrasted greatly with the pretty picture postcard scenes that typically "documented" America at that time. Although his photographs were severely criticized by photography experts, Frank inspired future generations of photographers who realized that the subjects for photography were not limited to traditional, postcard views.

Photographers such as Diane Arbus, Bruce Davidson, Lee Friedlander, Danny Lyon, Mary Ellen Mark, and Garry Winogrand use a shooting style that opened the streets to subjects previously not photographed.

Magazine photographs developed a more casual visual style as many of the "street photographers" freelanced for the magazines. Magazine images are usually more graphically complicated than straight-forward news photographs because readers spend more time viewing an image in a weekly or monthly magazine.

Curiously, magazine images of hard news subjects can be much more graphically violent and threatening to an ordinary person's privacy without the typical reader uproar found with similar images published in a newspaper. Readers have a more protective, almost personal commitment to their hometown newspaper. Nevertheless, newspaper photographers started to imitate the candid shooting style seen in the magazines. When that style is used for spot news situations in newspapers, subjects and readers sometimes object that their privacy has been violated.

News Photographer magazine has printed several articles that detail the right to privacy of a photographer's subject. In an article titled, "'Inside Story' Inside Photos," a television program hosted by the former state department spokesman for President Carter, Hodding Carter, featured a discussion of controversial images. Editors and photographers in the program generally agreed that a newspaper's mission is to sometimes make people uncomfortable. Although it is unfortunate that people complain when their anonymity is taken away when their picture is published, Hal Buell of the Associated Press remarked that if newspapers do not print pictures that upset people once in awhile, "Don't we stand a chance of the reader losing his credibility in the newspaper?" ("Inside story," 1982, p. 30).

Some critics complain that deadline pressures and competitiveness are responsible for journalists sometimes trampling on the privacy of others. Zuckerman (1989) noted that "News organizations, driven by intense competition, rarely let concern for a victim's privacy get in the way of a scoop" (p. 49).

Hilda Bridges Sues for Her Privacy

A woman in Florida did more than complain about the loss of her privacy. She sued the newspaper for millions of dollars. Hilda Bridges was kidnapped by her estranged husband, Clyde Bridges and forced to remove all of her clothes. He thought that his wife would be unwilling to escape if she were nude. When police surrounded the apartment building, Bridges killed himself. Behind police lines, Scott Maclay of the Cocoa Today newspaper was waiting with a 300mm lens. The photograph Maclay made shows a frightened woman, disrobed, but partially covered by a dishtowel, running with a police official who's face shows deep concern with his hand firmly grasping the woman's shoulder. After several hours of consultation with various editors, Maclay's picture of Hilda Bridges' rescue ran large on the front page. The newspaper's editor said that the picture "best capsulated the dramatic and tragic events" (Hvidston, 1983, p. 5). Some readers later complained that the picture of the scantily clad woman was published to sell additional copies of the newspaper and for no other reason.

Bridges claimed that her privacy had been invaded because she was naked. She testified that the photograph made her want to "crawl away, hoping nobody would see me." A lower court awarded the woman $10,000. On appeal, the decision was overturned. The key in court cases seems to hinge on the conduct of the news photographer or the news medium. "If the conduct is so extreme, so 'beyond all possible bounds of decency' . . . then one may be found guilty of intentional infliction of emotional distress" (Hvidston, 1983, p. 5).

The court in the appeal said that the picture "revealed little more . . . than some bathing suits seen on the beaches. The published photograph is more a depiction of grief, fright, and emotional tension than it is an appeal to other sensual appetites." Furthermore, the court said, "Because the story and photograph may be embarrassing or distressful to the plaintiff does not mean the newspaper cannot publish what is otherwise newsworthy" (Johns, 1984, p. 8).

Ron Galella and Jackie Onassis: Celebrity Photographs

A classic example of a photographer overstepping the bounds of decency was Ron Galella. Galella had one passion in his life-to photograph Jackie Onassis and her family. It was a lucrative passion. He once earned over $20,000 a year just for his pictures of Onassis. But Galella was no "one shot wonder." He followed Onassis and her family wherever he could. Galella was seen taking pictures of her while hiding "behind a coat rack in a restaurant, jumping out from behind bushes into the path of her children, and flicking a camera strap at Onassis while grunting, 'Glad to see me back, aren't you Jackie?" Galella even disguised himself as a Greek sailor and made pictures of Onassis sunbathing in the nude on the island of Scorpios. The pictures were later published in Hustler magazine.

Galella claimed he was simply exercising his right as a journalist under the First Amendment. In two courtroom decisions, (he simply ignored the first decision that ordered he stay at least 25 feet from Onassis) the court said he was guilty of "acts of extremely outrageous conduct." To avoid a possible 6-year prison term and a fine of $120,000, Galella signed an agreement to "never again aim a camera at Mrs. Onassis or her children" ("Photographers pledge," 1982, p. A-27).

Thousands of dollars and careers can be made by photographing famous people either doing extraordinary or quite ordinary actions. Readers seem to enjoy seeing famous people in ordinary situations given the popularity of the publications that use the images and the high prices editors pay to photographers for their pictures. Pictures that show the windblown skirts of a queen, the bikini look of a pregnant princess, and a president slipping down a plane's steps have earned large paychecks for the photographers. The foreign and national press have a tremendous interest in star-studded photographs as the popularity of personality publications and "infotainment" television programs attest.

Photojournalist Ross Baughman suggests that pictures of famous people undergoing ordinary activities need to be taken. Such pictures "can play an important role in democratizing royalty or in letting the public know these people are only human like the rest of us" (Johns, 1984, p. 7).

The intense competition among photographers to come up with unique angles of famous people have led to some obvious excesses. Six helicopters filled with photographers flew over the wedding of movie stars Michael Fox and Tracy Pollan. Recently, photographers have drawn criticism from the public and their colleagues by confronting a famous person until a reaction is visually demonstrated. Comedian Eddie Murphy was recently badgered by a photographer until he angrily reacted. The photographer then took the unflattering portrait of Murphy. Other celebrities such as Cher, Sean Penn, Meryl Streep, and the bodyguards for Prince have all had recent confrontations with overzealous photographers with some resulting in criminal action (Stein, 1988).

Louisiana State University journalism instructor Whitney Mundt said, "The furtive manner in which paparazzi operate in order to track down famous individuals is inherently unethical." Mundt suggested that photojournalists should not photograph famous people simply because they have familiar faces, but wait until they are involved in a situation that has "intrinsic news value" (cited in Johns, 1984, p. 8). A photographer who saw Zsa Zsa Gabor walking her dog would avoid taking her picture, according to Mundt's standard. A photographer, however, who saw Gabor slapping a Beverly Hills policeman would take the photograph. Such a standard, according to Mundt, "would have photojournalism which is no longer exploitive, and would no longer endanger the credibility of the press." The trend in that direction may have started with the publisher of The People newspaper in London who fired his editor for printing pictures of 7-year-old Prince William urinating in a public park ("London editor," 1989).

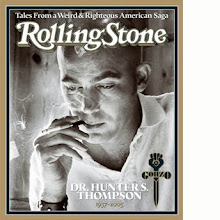

Although photographers have been criticized for their over-zealous candid coverage of the rich and famous, studio portraits of stars, for the most part, are carefully controlled public relations pictures. Jim Marshall, a photographer represented in the book, Rolling Stone The Photographs, criticized the magazine for accepting the strict photographic demands of stars and their representatives. "The stakes are much higher now," Marshall explained, "and with that kind of money at stake, everybody is very edgy about everything. Now we're seeing only what the artists and their managers want us to see. I think we are the lesser for it" (Sipchen, 1989, p. E- 1).

FOUR AREAS OF PRIVACY LAW

A quarterly publication of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press titled, "Photographers' Guide to Privacy," is helpful in sorting out the areas of privacy law that affect news photographers. Privacy law is divided into four areas:

* unreasonable intrusion into the seclusion of another,

* public disclosure of private facts,

* placing a person in a false light in the public eye, and

* misappropriation of a name or likeness for commercial gain (Strongman, 1987).

Unreasonable Intrusion

Consent is the most important factor when dealing with unreasonable intrusion or public disclosure of private facts. Generally, anything that can be seen in plain, public view can be photographed. Pictures in private places require permission. A photographer must be sure that the person who gives permission has the authority to grant the request. Some states will not accept the authority of a police or fire official or a landlord for a photographer to enter a private home. Written consent is preferred over oral consent. The Galella case was certainly an example of unreasonable intrusion on public property. The Lindbergh case was another.

Disclosure of Private Facts

Trespass laws require that photojournalists have the permission of an owner of a property before access can be gained. However, court rulings have sent mixed messages. A tenant at an alleged substandard apartment complex in Philadelphia gave permission to a television crew to enter the property. The landlord sued, but loss the case. Permission from a tenant is acceptable. A Kansas film crew lost its case when it was shown they used deceitful methods to obtain permission to film a nonpublic area of a restaurant. Misrepresentation is not acceptable. A Florida newspaper photographer was found not guilty of trespassing after obtaining permission from police and fire officials to photograph the body remains of a young girl killed in a fire. Permission from police officials is acceptable. However, that same Florida Supreme Court upheld a lower court decision in the case of a television crew who obtained permission from police officials to enter a private home that was part of a drug raid. States have different laws for journalists and trespassing. Editors should put together a package with the newspaper's legal representatives for all journalists on their staff telling them the trespassing laws that apply in their state (Sherer, 1986a).

False Light

Dr. Michael Sherer (1987) of the University of Nebraska explained the concept of false light. "Generally speaking," Sherer wrote, "a photojournalist can be found guilty of false light invasion of privacy if a person's image is placed before the public . . . in an untrue setting or situation" (p. 18). For there to be a false light decision against a photographer, the image must be highly offensive to a reasonable person, the photographer must have known that the image was false, or the photographer acted "with 'reckless disregard' (in other words, did not care) about whether the information was true or not" (p. 18).

The publication of a "stoutish" woman was ruled acceptable as the court noted, "There is no occasion for law to intervene in every case where someone's feelings are hurt." Filming by a camera crew of a man holding hands with a woman who was not his wife was ruled "not an act of extremely outrageous conduct." A person accidentally identified falsely in a caption does not constitute outrageous conduct. However, the publisher of Cinema-X magazine was cited for a "misidentified . . . photograph of a nude woman in a section of the magazine featuring I aspiring erotic actors and actresses' " (Sherer, 1986b, p. 26).

Misappropriation

The fourth area of trouble for a photojournalist in a privacy case is using a person's image for monetary gain without that person's permission. Clarence Arrington sued the New York Times for a picture it printed on the cover of its Sunday magazine illustrating an article, "Making It in the Black Middle Class." Arrington's "suit for invasion of constitutional and common law right to privacy was dismissed, but his complaint based on the sale of the photograph (by Contact Press Images-CPI-to the New York Times) was upheld in the New York Court of Appeals." The newspaper could not be sued because of the First Amendment protection, but CPI and the freelance photographer, Gianfranco Gorgoni, could have a claim against them. Unfortunately, the case was settled out of court without a ruling that might have protected picture agencies and freelance photographers (Henderson, 1989). A photographer may have the right to photograph anyone in public, but problems will occur when that image is published and is used to represent a class of individuals without that person's consent (Coleman, 1988). Freelance photographers need to be especially careful. One of the main reasons magazine editors and picture agency managers require releases from freelance photographers is to protect them from lawsuits by subjects.

When covering a news event, courts have ruled that photographers do not have to conform to rigid rules required for a subject's consent. Nevertheless, news media organizations are sometimes sued by individuals who argue that because the newspaper makes money, their violation of privacy case is valid. Most of these cases go in favor of the news organization on appeal because of the newsworthiness of the images. Freelance photographers, as Sherer (1987) noted, "need to pay special attention to the appropriation concept. There have been cases in which the selling of a photograph without the permission of those in the image had been held to be an appropriation of the person's likeness" (p. 18).

The Where and When of Picture Taking

Because many readers react strongly to pictures that seem to violate the privacy of others, it is important to be clear on the legal and ethical issues surrounding the right to privacy. An editorial writer in a 1907 edition of The Independent commented, "As regards photography in public it may be laid as a fundamental principle that one has a right to photograph anything that he has the right to look at" ("The ethics and etiquette," 1907, pp. 107-109). Such a declaration is not true for today's more complicated society, however. Ken Kobre (1980) in his textbook, Photojournalism The Professionals' Approach listed where and when a photojournalist can take pictures:

Where and When Pictures Can be Taken

Public Area

Street (Anytime)

Sidewalk (Anytime)

Airport (Anytime)

Beach (Anytime)

Park (Anytime)

Zoo (Anytime)

Train station (Anytime)

Bus station (Anytime)

In Public School

Preschool (Anytime)

Grade school (Anytime)

High school (Anytime)

Univ. campus (Anytime)

Class in session (Permission)

In Public Area--With Restrictions

Police headquarters (Restricted)

Govt. buildings (Restricted)

Courtroom (Permission)

Prison (Permission)

Legislative chambers (Permission)

In Medical Facilities

Hospital (Permission)

Rehab. center (Permission)

Emergency van (Permission)

Mental health center (Permission)

Doctor's office (Permission)

Clinic (Permission)

Private but Open-to-the-Public

Movie theater lobby (If No Objections)

Business office (If No Objections)

Hotel lobby (If No Objections)

Restaurant (If No Objections)

Casino (Restricted)

Museum (Restricted)

Shooting from Public Street into Private Area

Window of home (Anytime)

Porch (Anytime)

Lawn (Anytime)

In Private

Home (If No Objections)

Porch (If No Objections)

Lawn (If No Objections)

Apartment (If No Objections)

Hotel room (If No Objections)

Car (If No Objections)

If photographers persist in harassing their subjects, courts can further limit their actions in public and with famous persons. If courts can limit the actions of photographers making images of famous individuals, there may come a time when injured and grieving subjects are ruled off limits by sympathetic courtroom decisions as was done in some countries during the early years of photography.

Legal rights should not be the guiding principles for ethical consideration. What is legally acceptable is not always the right action to take. Staff photographer Sherry Bockwinkel of the Bellevue, Washington Journal-Gazette photographed a photojournalist who learned a lesson about the ethics of privacy. During a rope-descending performance, a Japanese acrobat fell to his death. A television videographer moved close to the scene as attempts were made to help the dancer. Suddenly a spectator angrily pushed him back. Although the news event occurred on a public sidewalk in downtown Seattle, managing editor, Jan Brandt wrote that the videographer "had moved into a sensitive area. Bockwinkel defines it as personal space, others call it invading privacy. His presence had become an intrusion seen and felt by those close to the scene and the feeling spilled over onto other photographers" ("Boundaries," 1986, p. 24).

A photographer must be aware of the privacy laws that apply to his or her jurisdiction, but that photographer must also realize that credibility, a highly valued principle, might be lost if a publicly grieving or famous person is unduly harassed.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Ghadiali earlier served with Amazon's growth arm Lab126 as main product or service supervisor, implementing the business's distinctive line of Ipad goods. He's got kept several other product or service supervision positions along with technology firms, which includes Horsepower and Synaptics.

ReplyDeleteFIFA 15 Coins IOS

FIFA 15 Coins PC

Maaf saya tidak bisa bahasa inggris dan saya tidak tau harus komentar seperti apa. terima kasih.

ReplyDeletehormat kami : Toko Timur

->>>>

? Penghilang Tato

? Vimax

? Obat Hernia

? Vimax Asli

? Model Kondom

? Obat Vimax

? Alat Bantu Seks

? Pembesar Penis

? Crystal X Original

? Crystal X

? Pemutih Kulit

? Pelangsing Badan

? Pembesar Payudara

? Lintah Oil

? Cara Menghilangkan Tato

? Agar Cepat Hamil

? Penyubur Kandungan

? Obat Kuat

? Obat Kuat Oles

? Obat Tradisional

? Kondom

? Kondom Antik

? Kondom Silikon

? Alat Bantu Sex

? Penis Palsu

? Celana Hernia

ReplyDeleteSorry sir, I have this backlink service manual and that I do. thank you

- Cara menghilangkan tato

- Kosmetik asia

- Toko solo

- Toko barat

- Bali jakarta

- Pusat kota

- Obat pembesar penis

- Obat vimax

- Penghilang tato

- pembesar penis

- Vimax asli

- Vimax original

- Pelangsing herbal

- Vimax canada

- Alat bantu sex

- Penghapus tato

- daerah wanita

- Cara menghilangkan tato